Reggio Magic: Open-Ended Playthings

Part One: THE PLAY DOUGH

Something old: Last week, I put a new invitation out on a table: freshly made lavender-scented play dough and familiar tools — our play dough scissors and small kitchen knives.

Something new: A basket of shiny glass stones, and a basket of small assorted stones from outside.

All week the children played with them, enchanted by the feel of the stones — smooth and rough, shiny and dull, of different weights. They pressed them into the playdough, hid them in the dough, stacked layer of stones and dough, each child calmed by the lavender, and absorbed in a little world of their own making.

Over the week we saw ice cream, burgers, snowmen, islands, an apple, Mickey Mouse, a house, a road, snakes, a rock castle, a cake. As they played, they talked about their creations; their hands squeezed, rolled, cut, and pinched; they became more familiar with scissors; they talked about colors; they shared stones and tools; they started to notice one another’s creations and became inspired to do more.

Over the week we saw ice cream, burgers, snowmen, islands, an apple, Mickey Mouse, a house, a road, snakes, a rock castle, a cake. As they played, they talked about their creations; their hands squeezed, rolled, cut, and pinched; they became more familiar with scissors; they talked about colors; they shared stones and tools; they started to notice one another’s creations and became inspired to do more.

Once again, for the millionth time, I fell in love with open-ended playthings.

Open-ended materials for young children are materials without a pre-determined script. They can be used and manipulated in many ways, limited only by the children’s imagination. Not only do children practice motor, language, and social skills with them, but they also encourage imaginative play. Imaginative play — the cornerstone, the essence, and the driving force of young children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development.

Watching the children so enraptured by the play dough and stone combination, I thought it might be fun to choose another familiar classroom open-ended material and reflect on its many uses.

Part Two: THE SILK SCARF

One of the most important objects in our classroom is our basket of brightly colored silk scarves. How does a simple silk scarf make its way through the school day of our two- and three-year-olds?

HIDING

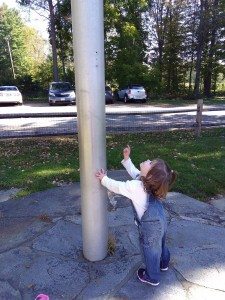

Under the scarf, we hide ourselves, toy animals and little people, a drum, a block, a ball! Even more fun, we hide each other!

We dance, parade, wiggle, and shake. We wave the scarves high and spin them around us. We run across the gym with them, flying like the wind!

SLEEP

We use it as a blanket for ourselves–and for our babies!

PREPOSITIONS

We hide UNDER it. We pass it THROUGH our legs. We drape it OVER us. We sit ON it. We wave it AROUND us. We wave it ABOVE us. We put them IN the basket.

VISION

We look through it and see the world tinted in color.

On a picnic! (the scarf is our blanket) To the beach! (the scarf is our towel) To the store! (the scarf is our coat) To the rescue! (the scarf is our cape).

BABIES

We use the scarves to swaddle them, and to lay over them on their beds.

SOUND

When we wave them hard, they make a little “snap.” When we cover the big drum with them, they muffle the drum beat.

TOUCH

They flutter over our faces and our arms. They feel soft on our skin.

AN IMAGINATIVE PLAY UNIFORM!

Sometimes while wearing their scarves, the children go about their business, cooking in the play kitchen, drawing, or playing in the dollhouse.

At these times, the scarves are like Superman’s transforming cape, empowering the children with greater focus and imagination, and enabling their young brains to soar!